Decision Making Under Extreme Uncertainty: Lessons in Data Trust with Annie Duke

Have you ever had to make a decision when you don’t have all the facts? If you’re nodding your head, welcome to the club!

The good news?

There are some tips and tricks you can apply to make good decisions with less data – or think in bets.

At IMPACT 2023, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Annie Duke, former professional poker player, professional decision strategist to discuss how to make smarter decisions from limited data, how teams can establish better decision-making processes, and when to know if that “gut feeling” is worth trusting.

Check out the full session here:

Table of Contents

What it means to ‘think in bets’

One thing we know firsthand? The seminal importance of good data. Businesses everywhere rely on data to guide them in their decision making in uncertain situations.

But how do we know if the data we have is enough to make the right decision – or not?

For Duke, “thinking in bets” means shifting the narrative to focus on the outcome of the decision rather than the decision making process itself. “Thinking in bets,” she says, “is understanding that outcomes are influenced by both skill and luck.”

This perspective acknowledges the fact that the data we know may not be representative of the whole picture – but that doesn’t mean you should hold off on making a decision as a result.

As Duke explains, “All of us have limited resources – time, money, etc – and we can only invest those into a certain number of options across our lifetimes. Each option we choose has, associated with it, a certain number of outcomes and a certain probability of each of those outcomes occurring.”

So, thinking in bets doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re slapping money on the table and hoping the dice roll in your favor. Thinking in bets is a type of probabilistic thinking: understanding that there’s a certain probability that the outcome you want can occur – and it might be due to your decision-making process, but it also may be due to external factors, like luck or chance, as well.

Does it make decision-making easier? You bet (pun intended!) it does. Let’s explore how.

How ‘resulting’ can actually ease decision-making processes

Duke introduces the concept of resulting in her book “Thinking in Bets.” The act of “resulting” refers to the tendency to judge the quality of a decision based on the outcome that follows. When evaluating a decision, we tend to look at the result and assume that the outcome reflects the quality of the decision-making process alone.

“Resulting indexes heavily on the outcome,” says Duke. “But you might have had a perfect decision making process, and you were just dealt a bad hand.”

Duke explains that judging the quality of your decision making rather than the quality of the outcome is a flawed approach to decision assessment, because it doesn’t necessarily take into consideration the factors that are out of your control.

Even a well-thought-out decision can lead to a negative outcome due to external factors, and conversely, a poor decision can sometimes result in a positive outcome if luck is on our side.

What does a good decision-making process look like?

“Good decision making processes keep a record for you,” says Duke. “For data people, that generates a tremendous amount of data around the decision making process.”

As much as possible, teams should track the steps that were taken as part of the decision making process. Every question, consideration, and perspective during the decision assessment process is data to be leveraged in the future.

“If you’re a team and you’re keeping a record of the decision making process, you’ll be able to look back on the decision context,” says Duke. “So no matter what happens, whether you got the outcome you wanted or not, you can go back and understand what you were thinking at the time.”

This process is also helpful for revealing what information was made available after the outcome. This hindsight bias is easy to fall prey to, especially if the outcome was favorable. It can convince your team that you knew you were making the right decisions all along.

Keeping a record of the decision making process is crucial for both independent and teams to understand which of their decisions may have led to the outcome and what can be attributed to external factors.

However, when it comes to making decisions as a team, there are some common pitfalls to avoid…

Teamwork makes the decision-making dream work – but only when done right

“Most of the problems with decision making occur because we work on decisions in a group setting,” says Duke.

Sounds a little counterintuitive, but stay with me. “That’s not to say that I think teams are bad for decision making. I think teams are good for decision making. But, they’re only good if you utilize the team in a way that will actually improve the decision making.”

Typically, Duke explains, we think a group is brought together to do three things: discover, discuss, and decide. Or, as I’d like to call it, Triple D (and no, I’m not referring to Guy Fieri’s Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives).

Groups come together to discover the perspectives that other group members hold, discuss those perspectives to understand them better, and then, based on the first two actions, decide on a consensus.

That’s a pretty familiar meeting agenda, at least as far as I’m used to. But, just because we’re used to that group format does not mean it’s the most effective.

Duke argues that a group setting is actually only good for one of those actions: discussion.

Discovery and decision making should then be done in nominal groups first, which means individuals work independently before they come together as a group to make a decision.

Take the example of hiring a new data engineer for your team. The candidate goes through interview rounds with several stakeholders, and then you all might hop on a call or into a conversation on Slack to share your thoughts. If one person – especially someone at a higher level in the company or with a longer tenure – shares their positive feedback about the candidate, their opinion may seem like the right one by default. There’s a high likelihood that others in the group may soften their original critical feedback because the stakeholder with more “sway” expressed a different opinion. This kind of indirect “groupthink” is a direct result of group decision making.

Duke believes nominal groups are a more effective way to share decisions. A hiring process with nominal group decision making may look something like this:

- Candidate goes through all interview rounds

- All internal interviewers independently evaluate the candidate, ideally on a scale, and keep their answers private.

- When all answers are complete, they’re all made available to everyone on the hiring committee at once.

- As a group, the team discusses the results and evaluates discrepancies in answers.

- Based on these objective opinions, the group makes the decision.

This kind of decision-making model is important, because it reinforces a key truth in decision making and in data: even if we have the same facts, we can model them differently.

“And,” Duke continues, “even if we have the same model, we still may make a different decision because we might have different risk attitudes. So the additional perspective aids in reducing cognitive and confirmation bias.

“We need to change what we think it means when we talk about being on the same page,” says Duke. And at the root of consensus? Trust. In the data, in the process, and in the decision.

In business, data trust is at the center of decision-making

Effective decision making is crucial for data-driven organizations. But to make effective decisions, you need to not only trust in the decision-making process – you need to trust in the data that’s informing it.

Does a gut feeling count as trustworthy data? Duke says probably not. “You should only solely follow your gut for decisions where it doesn’t matter if you introduce errors.” So, kind of like me choosing chicken in my burrito when my gut was telling me steak. (Why don’t I ever listen!)

When it comes to data-driven organizations, making decisions without high quality is tantamount to following your gut. Because, if you can’t verify the health of your data, you can’t verify the veracity of the insights. It’s a metaphorical gut-feeling in this sense because it introduces ample opportunities for error and lost value.

So, it’s important to stick to decisions that are built on trustworthy data. On a practitioner level, the highest quality and most trustworthy data is data that’s constantly being monitored and validated. Trusted data delivers trusted decision insights.

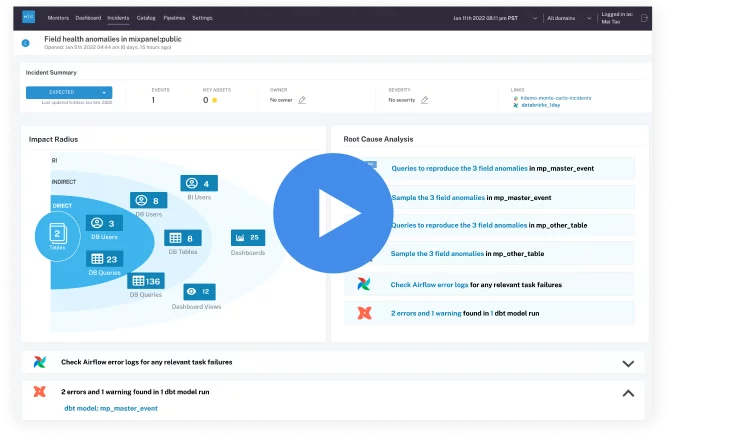

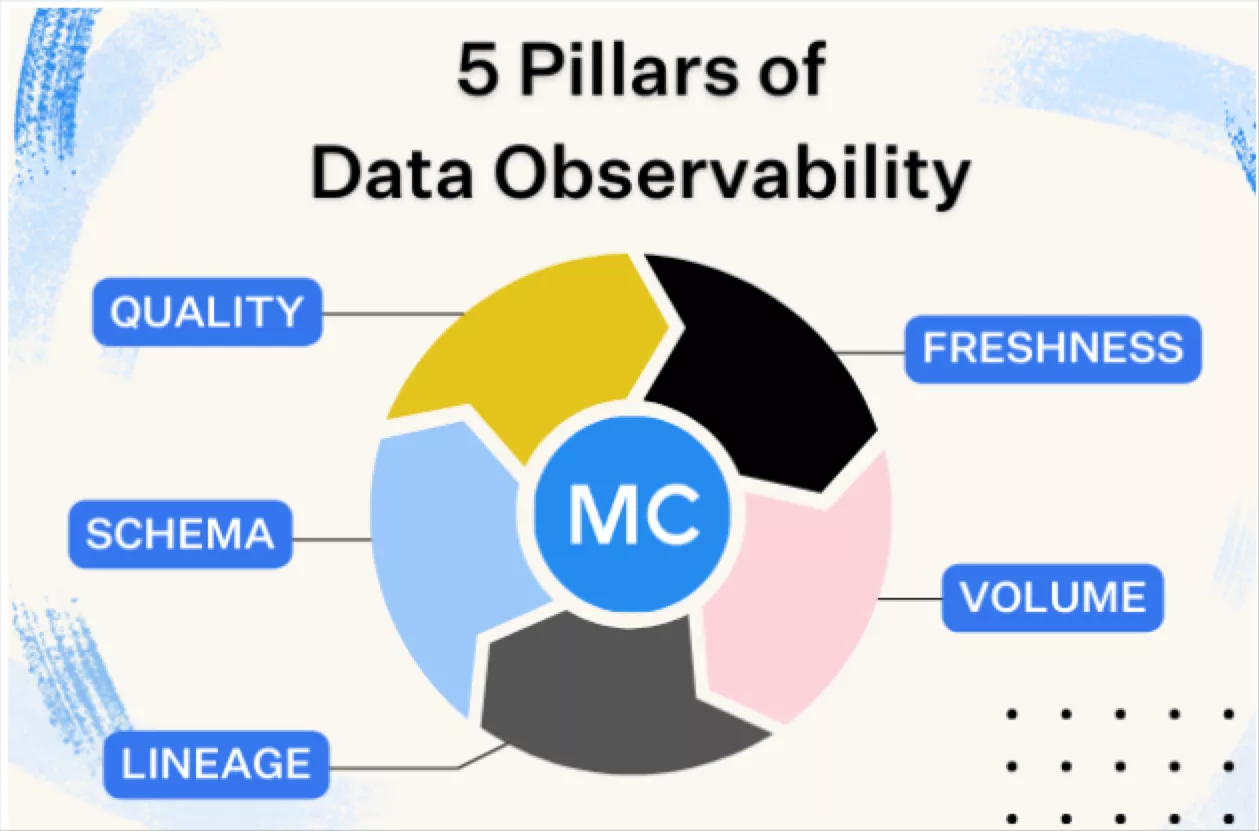

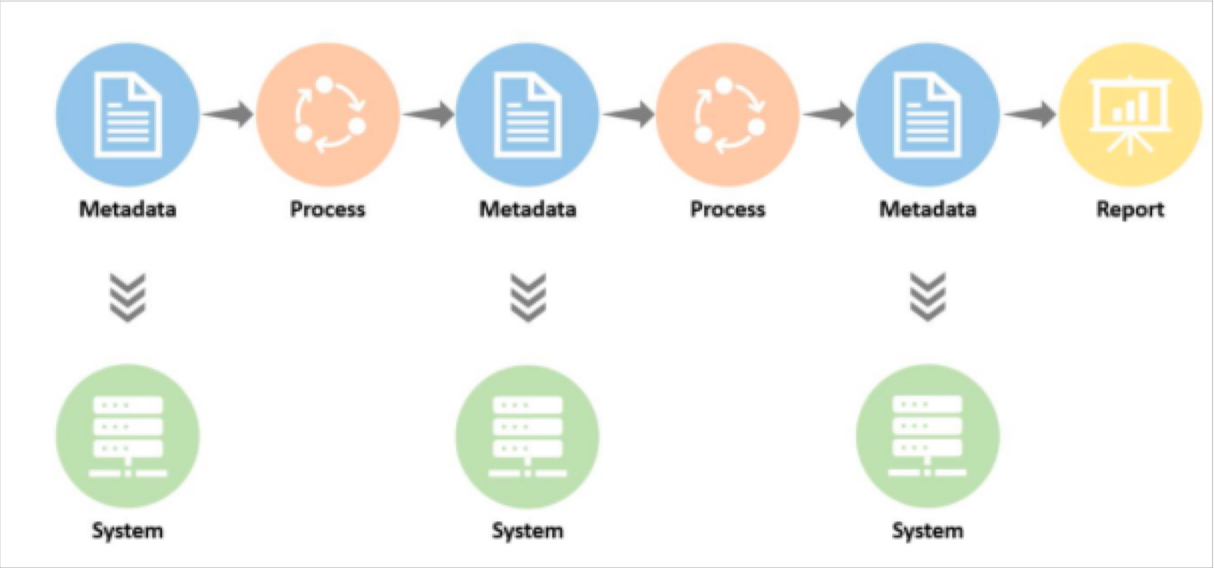

A solution like data observability helps teams proactively detect, resolve, and prevent data quality issues at scale with automated monitoring and alerts for issues like freshness, schema, and volume, and comprehensive data lineage to pinpoint and remediate issues faster.

To learn more about how Monte Carlo can help your team build data trust, drop your email in the form below, and let’s talk!

Our promise: we will show you the product.

Product demo.

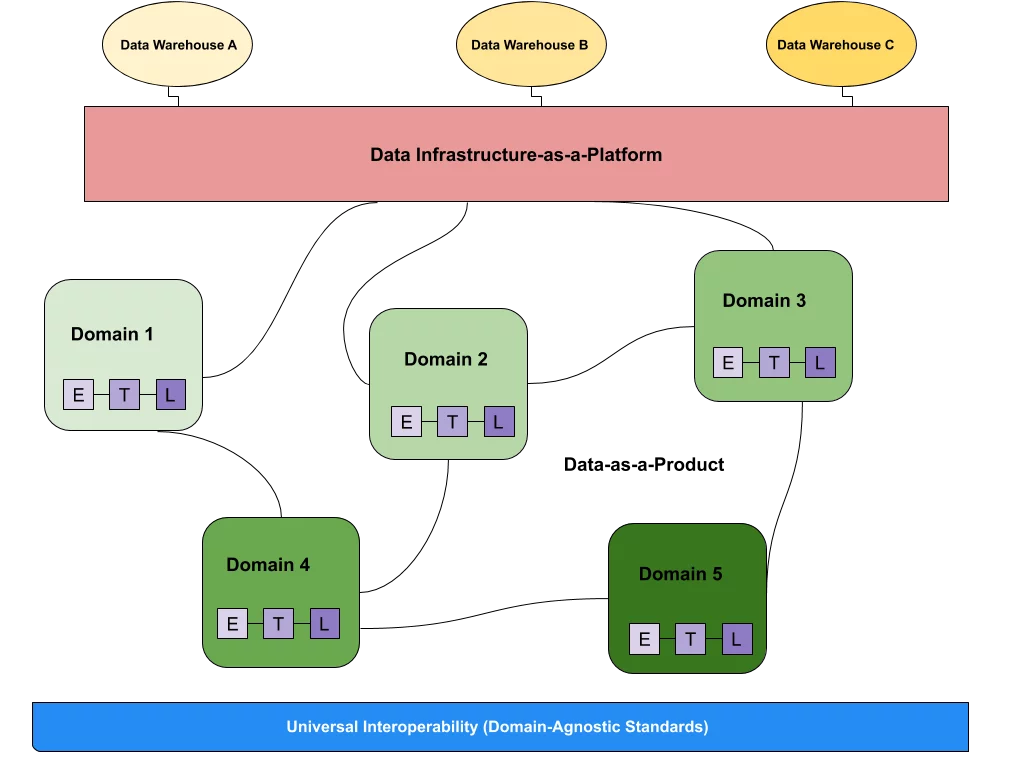

Product demo.  What is data observability?

What is data observability?  What is a data mesh--and how not to mesh it up

What is a data mesh--and how not to mesh it up  The ULTIMATE Guide To Data Lineage

The ULTIMATE Guide To Data Lineage